According to a readout provided to the press by the Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo met with Vietnamese PM Phạm Minh Chính on September 19, 2023 and “pledged to urge the U.S. to soon recognize Viet Nam’s market economy status.”

What does this mean and what can be expected from the Secretary’s reported comments?

Non-Market Economy Status in International Law

Pursuant to the World Trade Organization agreements (GATT Article VI), importing countries may deem an exporting country to be a “non-market economy” country for the purposes of applying domestic anti-dumping duty laws. Normally, dumping is determined by comparing export prices to domestic home market prices or cost of production (called “normal value”). Where the export price is lower than home market prices or costs, that is dumping. Dumping that causes or threatens to cause material injury may be offset by duties. But, for exporting countries in which the government has a significant role in trade and domestic pricing — “non‑market economies” — an importing country may derogate from comparing export price to home market sales prices or costs. Prices and costs from an analogous market economy country (called a “surrogate” or “analogue”) may be used in place of prices or costs in the non-market economy. Each importing country’s investigating authority has discretion to determine which exporting countries it considers non-market economies.

In effect, the non-market economy provisions allow an investigating authority to identify non-market economies and “move” the exporting entity out of the non-market economy country by approximating prices and costs that would have been charged or incurred in a similar market economy country.

Non-Market Economy Status in U.S. Law

Commerce considers the following countries to be non-market economy countries for the purposes of U.S. anti-dumping duty law:

- Republic of Armenia (see 57 FR 23380)

- Republic of Azerbaijan (see 57 FR 23380)

- Republic of Belarus (see 57 FR 23380)

- People’s Republic of China (see 82 FR 50858)

- Georgia (see 57 FR 23380)

- Kyrgyz Republic (see 57 FR 23380)

- Republic of Moldova (see 57 FR 23380)

- Russian Federation (see 87 FR 69002)

- Republic of Tajikistan (see 57 FR 23380)

- Turkmenistan (see 57 FR 23380)

- Republic of Uzbekistan (see 57 FR 23380)

- Socialist Republic of Vietnam (see 68 FR 37116)

In Section 771(18) of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (the “Tariff Act”), Congress set forth six factors for the U.S. Department of Commerce (“Commerce”) to consider in determining whether an exporting country “does not operate on market principles of cost or pricing structures, so that sales of merchandise in such country do not reflect the fair value of the merchandise” — in other words, whether it is a non-market economy:

- the extent to which the currency of the foreign country is convertible into the currency of other countries;

- the extent to which wage rates in the foreign country are determined by free bargaining between labor and management,

- the extent to which joint ventures or other investments by firms of other foreign countries are permitted in the foreign country,

- the extent of government ownership or control of the means of production,

- the extent of government control over the allocation of resources and over the price and output decisions of enterprises, and

- such other factors as the administering authority considers appropriate.

As these are highly fact-dependent and require the application of agency expertise, Congress has not provided for judicial review of Commerce’s determination (19 U.S.C. § 1677(18)(D)) and maintains each non-market economy designation in effect until it is revoked (19 U.S.C. § 1677(18)(C)).

Practical Impact of Non-Market Economy Status

Where an importing country designates an exporting country as a non-market economy, the practical impact is that the importing country may use alternative bases for determining whether dumping is occurring. In the United States, whenever merchandise under an anti-dumping investigation or review is exported from a designated nonmarket economy country, Section 773(c) of the Tariff Act permits Commerce to change how it calculates the “normal value,” i.e., the benchmark for assessing the presence and degree of dumping in the United States. Specifically, Commerce may forego the use of non-market economy prices or costs as normal value and instead determine normal value “on the basis of the value of the factors of production utilized in producing the merchandise and to which shall be added an amount for general expenses and profit plus the cost of containers, coverings, and other expenses.” 19 U.S.C. § 1677b(c)(1).

To do so, Commerce must first assess the actual experience of the non-market economy producer to determine its “factors of production,” e.g., hours of labor used, amounts of inputs and electricity consumed, etc. The statute then obligates Commerce to select values for each “factor of production” from “one or more market economy countries that are (A) at a level of economic development comparable to that of the nonmarket economy country, and (B) significant producers of comparable merchandise.” 19 U.S.C. § 1677b(c)(4). Commerce periodically reassesses which market economy countries are economically comparable to each designated non-market economy country. For example, an August 24, 2023 Commerce memorandum identifies Indonesia, Jordan, Egypt, Philippines, Morocco, and Sri Lanka as economically comparable to Vietnam based on their relative gross national income per capita in the most recently completed calendar year.

Therefore, under current practice, in any anti-dumping proceeding involving imports from Vietnam, Commerce may calculate normal value using prices and costs from one or more of the aforementioned six countries. Generally, a Vietnamese producer’s home market prices and costs may not be used in the calculating normal value, although their actual production experiences will be used. Normal value calculated in this way will, as in all dumping calculations, be compared to the producer’s actual U.S. sales prices.

By contrast, were Vietnam’s non-market economy status revoked, Section 773(a) of the Tariff Act would generally oblige Commerce to analyze Vietnamese dumping by comparing U.S. sales prices against Vietnamese sales prices and costs. Where Vietnamese sales prices and costs are distorted by the government’s outsized role in the Vietnamese economy, dumping may be understated or completely masked.

Commerce’s Most Recently Completed NME Analysis Revoked Russia’s Market Economy Status Because of Increased Government Intervention in the Market

In 2022, Commerce determined that the Russian Federation (“Russia”) will be considered a NME for anti-dumping calculation purposes. Although this determination was made against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Commerce nonetheless tethered its analysis to the six statutory factors described above and concluded that, for each factor, the Russian Government had significantly backtracked on earlier commitments to market economy reforms, including:

- Russia’s extensive involvement in currency markets, which has significantly impacted the ruble’s convertibility and exchange rate;

- Increasing limitations on investment by non-Russian firms in Russia;

- Increasing government involvement in the economy, including its increased use of state-invested enterprises, particularly in the energy sector, to support Russia’s war in Ukraine;

- Increasing government control over domestic prices and rising government influence in the banking sector; and

- Increasing levels of corruption and decreasing respect for the rule of law.

As shown in Commerce’s assessment of Russia’s market status, changes in government interventions can frequently happen for a variety of reasons. Rather than regularly revisiting its non-market economy designations, Commerce has instead sought to be assured that any liberalization of central government control is permanent and long-lasting to avoid the “yo-yo” impact of on-again, off-again market economy designations.

Independent Observers Note Reasons for Commerce to Scrutinize the Government’s Role in Vietnam’s Economy

To be sure, Vietnam has taken steps toward market orientation since Commerce concluded its most recent assessment in 2002, but “improvement” is not the statutory standard for market economy designation. Available evidence from independent observers indicates the persistence of conditions that could be considered substantial government intervention in Vietnam’s economy:

- The government imposes significant foreign ownership limits in the banking sector;

- The central bank, State Bank of Vietnam, is not an independent body and operates under strict government oversight;

- State-owned enterprises still account for at least one-third of Vietnam’s gross domestic product and dominate the energy, transport, telecommunications, and finance sectors; and

- Foreign direct investment remains strictly managed by the government.

The Sixth “Catch-All” Factor Is Also Likely to Be a Material Consideration as Concerns Vietnam’s Market Economy Status

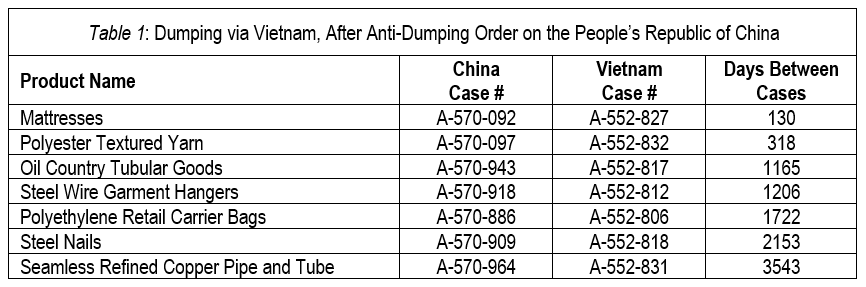

As referenced above, there are six statutory factors that Congress deemed appropriate for Commerce to consider in assessing a country’s market economy status. The sixth of these allows Commerce to consider any “other factors as {Commerce} considers appropriate.” 19 U.S.C. § 1677(18)(B)(vi). Doubtless, the statute’s broad language permits Commerce to take into account the fact that over the last decade, Vietnam has been the target of a successive dumping investigation seven different times after the original target – the People’s Republic of China (“PRC”) – was found to be engaged in injurious dumping. Within as little as 130 days after the date of the anti-dumping duty order concerning China, new producers in Vietnam were subject to ultimately successful allegations of dumping in the United States, as shown in Table 1:

And, just as often, Vietnam has been investigated for dumping simultaneously with Chinese entities. Across the simultaneous and successive cases, there are instances of overlapping affiliated relationships involving Chinese and Vietnamese entities.

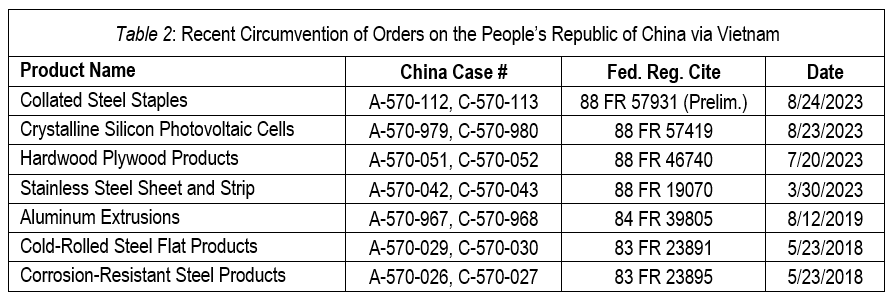

In addition, as shown in Table 2, Commerce has found Vietnam to be circumventing existing anti‑dumping duty orders on several occasions over the last five years. Such circumvention involves minor assembly operations in Vietnam using parts and components imported from a country (most often the People’s Republic of China) subject to anti-dumping and/or countervailing duty order(s).

The evasion and circumvention determinations noted above also coincide with Vietnam’s recent success in attracting foreign direct investment in response to the 2018 imposition of tariffs on Chinese goods pursuant to Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. To attract such FDI, Vietnam’s industrial zones provide preferential treatment to entities relocating from China.

Certainly, Commerce will scrutinize the government’s domestic role in Vietnam’s economy, but this is not the end of the statutory analysis. Any state-condoned efforts to facilitate Vietnamese production aimed at avoiding the impact of antidumping and countervailing duty orders on other non-market economies will likewise bear upon Vietnam’s status as a market or non-market economy in Commerce’s assessment.

Conclusion

As discussed, the decision to grant a country market economy status is subject to a rigorous fact-finding and assessment by career officials at the U.S. Department of Commerce. Therefore, interested parties will have opportunities to provide facts for Commerce’s consideration in assessing Vietnam’s status as a market or non-market economy. CLK is able to assist clients in this space.